Violet Spears was born to moderately prosperous farmers, on the outskirts of Elgin, Scotland, in 1839 (please see research notes at the end of the article). Of a dramatic mindset at an early age, Violet loved to draw, sing, and act for her family. Nonetheless, her first career was of the usual sort: she married 33-year-old farmer Henry Fitzpatrick at the age of 15, and had four children (including a set of twins) by the time she was 22.

Violet had no more children, and rumor had it that a complaining Henry began to stray. When she was 33, Henry died in a hunting accident of vague detail. Violet’s eldest had married by then, so she and her three remaining children went to live with her sister for two years of mourning.

On the second anniversary of her husband’s death, Violet disappeared. Her children were working the family farms by this time, so Violet left them with Nancy, along with three mourning dresses, piled on her bed. Despite her later dark reputation, she never work black again.

Nothing was heard of her for a year. At that time, small sums began to arrive monthly to Nancy’s family, delivered by messenger, along with a small sprig of violets.

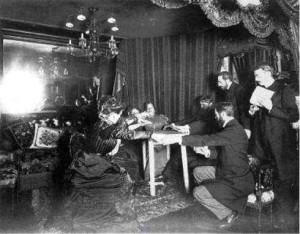

In 1876, medium and hypnotist Madam Violet began to attract notoriety in Edinburgh. By this time, the charasmatic spiritualist had gathered a small group of followers, whom she  affectionately referred to as her “hive.” Her seances had become more and more elaborate, using elements of phantasmagoria to awe her guests. Blood ritual was introduced gradually, with clients being asked to donate small amounts of blood to help “connect to the spirits.” Violet would drink the small goblet of commingled blood. She reported that it made her euphoric, that “this element, returned to me, had been missing the whole of my life.”

affectionately referred to as her “hive.” Her seances had become more and more elaborate, using elements of phantasmagoria to awe her guests. Blood ritual was introduced gradually, with clients being asked to donate small amounts of blood to help “connect to the spirits.” Violet would drink the small goblet of commingled blood. She reported that it made her euphoric, that “this element, returned to me, had been missing the whole of my life.”

Two years later, Madam Violet’s seances were a rare ticket. She abandoned her modest home to live with her Hive in the Edinburgh Vaults. Members of the Hive emerged only at night. They became known as lively but dangerous partiers, seducing the loveliest of men and women, and convincing them–often with the help of drugs and alcohol–to donate a bit of blood. Several of these victims were so enchanted, they left their lives behind and joined the Hive. Though no fatalities occurred, one or two injured parties did report Hive members to the police. The issues faded away quietly without arrest or resolution.

Hive members all bore the marks of a scarification device used in bloodletting, but they brought not only their blood, but their funds. The Hive was able to live in some comfort, even in the damp underground of the Vaults.

Hive members all bore the marks of a scarification device used in bloodletting, but they brought not only their blood, but their funds. The Hive was able to live in some comfort, even in the damp underground of the Vaults.

Violet herself did not leave the Vaults except to conduct seances, for which she wore elaborate “royal” costuming, as Queen of the Hive.

Violet herself did not leave the Vaults except to conduct seances, for which she wore elaborate “royal” costuming, as Queen of the Hive.

Some reports say that Madam Violet was “voted the most scary woman in England” in 1882 and 1884. As Violet never left Scotland, this is logistically unlikely. There was a mention of her in The Scotsman in 1881. An attendee of one of her seances described her as “most comely and frightening.”

The Hive continued to grow over the next decade, and included the son of a prominent council member. This was to be its undoing, when the young man developed an infection following a bloodletting, and subsequently died. The council member had the ear of Lord Provost, James Russell. Russell, a physician, condemned the Hive for their “unnecessary and excessive letting of humours,” and “acts immoral and vile,” and over the next few years, used his position to see them disbanded. The Vaults were raided and closed, and Madam Violet fled to Galashiels, where she lived with her few remaining Hive members.

Madam Violet died in 1930, at age 90. The last half of her life was spent living modestly and quietly with her Hive, giving only the occasional seance. Upon her death, her reputation denied her burial on consecrated ground, as well as the services of a stonemason. Her few remaining followers buried her outside the town, and created crude headstone.

Violet wrote little, but at the end of her life, she composed a short list of confessions, now preserved in the archives of the University of Edinburgh:

I poisoned my fifth child in the womb. I am not sorry.

I plugged the barrel of my husband’s rifle. I am not sorry.

I am sorry for poor Daniel’s death, I should have looked after him better.

Except for these, I hurt no one, though I am deemed by some to be wicked.I am not sorry.

RESEARCH NOTES: Much of this article was sourced from the book Vampires of Scotland by–oh, who am I kidding. I totally made this up. I saw this photo with its fake caption, and was sad it wasn’t for real. The pictures (except for the seance) are Polish actress Mari Jászai. The headstone and some early life details are from this guy’s genealogical research. The Edinburgh Vaults really exist, and are pretty cool.